It seems like a lifetime since the diesel boom of the late nineties and 2000s, incentivised by lower tax rates for diesel cars, saw petrol drivers move over to the fuel in their droves.

In 2015 diesels had a massive 48.5% share of the new car market. Yet by 2023 that market share had fallen to just 8% and continues to drop year-by-year.

So what happened? Why was diesel all the rage one decade and then a dirty word in the next? And should you buy a diesel car today over petrol, hybrid or electric car options? We explore the subject in our in-depth guide

The rise of diesel cars

A brief history of the diesel car

The diesel engine has been around almost as long as the petrol engine, invented by German engineer Rudolf Diesel in the 1890s. Its first applications during the early 20th century were in mining, manufacturing and marine powerplants.

By the 1930s the diesel engine began to find its way into automobiles. Although ever-innovative Citroen was the first to introduce a diesel option in a car with the 1933 Rosalie, it’s the Mercedes-Benz 260 D of 1936 that’s credited as being the world’s first mass production diesel car.

While diesels were praised for their durability and efficiency, these early examples were much noisier and slower than equivalent petrols. They mainly found favour in commercial vehicle applications until the oil crisis of the 1970s brought about more demand for fuel efficient engines.

It was here when German and French brands again lead the charge, with turbocharging addressing the performance problem of earlier diesels – Peugeot and Citroen’s ‘XUD’ diesel engine of 1982 was considered a game-changer, offering petrol-like performance, improved refinement and amazing fuel economy.

Engines like the XUD helped diesel sales in Europe surge, from just 2.5% of the market in 1973 to 11% by 1983.

1990s-2015 diesel boom – the focus on CO2

By the early 1990s diesel had gained mainstream acceptance in passenger cars. Targeted at high mileage business users and taxi drivers at first, by 1992 over 17% off the European car market was diesel.

But another boom was coming. In 1997, 41 countries signed the landmark Kyoto Protocol, an international treaty to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. One of the EU’s key responses to that was to promote diesel as the most eco-friendly fuel.

The key, said the EU, was diesel’s reduced CO2 (carbon dioxide) emissions – CO2 being named as the most dominant gas emitted by humans by burning fossil fuels.

The UK’s Labour government, led by Tony Blair, agreed. In 2001 Chancellor Gordon Brown sought to boost diesel’s already growing popularity with a new system of car tax (VED) – effectively a sliding scale that meant the less CO2 your car produced, the less you paid in annual tax.

This didn’t just affect private car buyers: company car tax reform to a CO2-linked system meant diesels were effectively the norm for business users by the mid-2000s – the motivation being mainly financial, rather than environmental.

Other countries adopted similar policies, and the rise in fuel costs of the late 2000s (brought about in part by the financial crash) further pushed buyers towards diesels, which were usually capable of 20% less fuel consumption than a petrol equivalent.

The peak of diesel’s popularity arrived in 2015: 52% of new cars sold across Europe were powered by the fuel. By 2017, there were more than 12 million diesel cars on Britain’s roads.

Cheaper than AA or we'll beat by 20%^

• Roadside cover from £5.49 a month*

• We get to most breakdowns in 60 mins or less

• Our patrols fix 4/5 breakdowns on the spot

Diesel exhaust emissions: a public health crisis

While diesel cars offered lower CO2 emissions, the engines at the time emitted vastly larger quantities of other pollutants contributing to poor local air quality and health issues. These included nitrogen oxides (NOx) and particulate matter.

Emissions of NOx are linked to a significant increase in respiratory problems such as asthma, while particulates from diesel engine exhausts are classed as carcinogenic (cancer-causing) and can also have respiratory effects.

Governments knew about these air quality concerns around diesel exhaust emissions in the early 2000s, but CO2 emissions were deemed to be the overriding issue of the time. Nevertheless, concerns are diesel emissions grew throughout the decade as more air quality studies made the link.

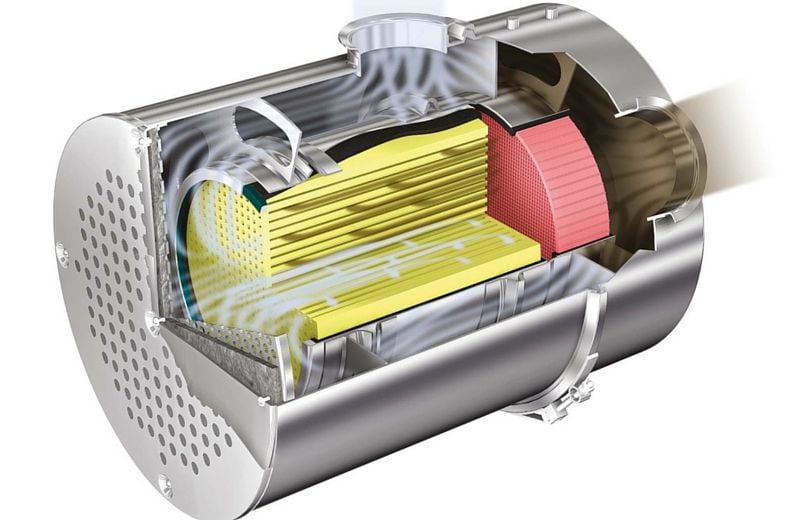

By 2009, growing air quality concerns had led the EU to introduce a new set of emissions standards, called Euro 5. Diesel particulate filters (DPFs) became mandatory fitment, substantially reducing NOx and particulate emissions of diesel engines.

But with millions of existing diesel cars, vans and trucks on the roads, it led the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer to officially categorize diesel exhaust emissions as carcinogenic to humans – this didn’t happen until 2012, however.

Pressure built on the UK government to reduce emissions after consistently missing EU targets to cut air pollution. Then, in 2014, a ruling by the European Court of Justice forced the UK to put actions in place to clean up its air quality – with the Government admitting that London, Leeds and Birmingham wouldn’t meet legal NOx emissions limits until after 2030.

By 2016, the Royal College of Physicians published a report claiming that around 40,000 deaths per year were linked to exposure to air pollution in the UK alone.

‘Dieselgate’ – the diesel emissions scandal that rocked the car industry

In 2013, the International Council on Clean Transportation commissioned researchers at West Virginia University to test emissions from diesel cars in real-world environments. Up until that point, tests had primarily been conducted in labs – tests which Volkswagen’s US-market ‘clean diesels’ had aced.

During live road tests the researchers found that Volkswagen diesels were emitting vastly more NOx than claimed – in some cases 20-35 times the US emissions limit, or more (source: WVU). The results were so bad the researchers initially believed they were making a mistake, so reran the testing multiple times.

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) received the results, and in September 2015 accused the VW Group of manipulating emissions tests using so-called “defeat devices”.

Volkswagen executives initially denied the claims, but eventually admitted that software had been installed that recognised when a car was undergoing lab testing and temporarily reduced NOx emissions. The software was fitted to 11 million diesel engines worldwide.

VW’s share price plummeted by 40% in two days, and CEO Martin Winterkorn stepped down – despite claiming he knew nothing about the defeat devices. Other regulators around the world began conducting their own investigations into VW Group vehicles.

The events that followed included Volkswagen recalling millions of 2.0-litre diesel models built from 2009-2015, as well as 3.0-litre diesels in Audi and Porsche models.

VW even had to buy back cars in the US, while billions of dollars of fines and penalties were levied at the brand. Volkswagen itself admitted in 2020 the scandal had cost them over $33 billion in fines, settlements and costs, but some legal action continues even to this day.

Diesel today and in the future – have diesel emissions improved?

While the fallout from Dieselgate still rolls on in the courts, the knock-on effects to the industry and car buyers have been significant.

Consumer confidence took a significant hit after the scandal. It wasn’t just views towards diesel vehicles that changed, confidence in published fuel economy and emissions testing had waned. Put simply, people didn’t believe the figures they were being told.

Regulators in Europe responded with much tougher, more real-world test procedures, brought out in 2017. These are the Worldwide Hamonised Light Vehicle Test Procedure (WLTP) and the Real Driving Emissions test (RDE).

Car companies also scrambled to clean up their diesel vehicle emissions to meet the 2014-on Euro 6 emissions regulations. Along with DPFs, technology such as exhaust gas recirculation (EGR) and AdBlue urea injection has helped to dramatically reduce these harmful emissions.

So yes, diesel car emissions have improved thanks to increased recognition of air quality issues and new technology. And diesels continue to have fuel economy and CO2 emission advantages over petrol, although the influx of mild-hybrid and full hybrid petrol models is making that advantage smaller.

However, most pre-2014 diesel cars do not meet the latest emissions standards.

Older models that don’t meet Euro 6 standards are still a problem with regards to air quality. This is why many cities in the UK and Europe either levy charges for older diesels entering the city limits, or ban them altogether, through Clean Air Zones such as London’s ULEZ.

Are people still buying new diesel cars?

In the US, the diesel passenger car market is effectively dead after the emissions scandal, but it still holds some popularity in the pick-up truck and large SUV sectors.

Volkswagen once had a massive foothold in the US with cars like the Jetta and Passat TDI, but the brand phased out diesels soon after the scandal emerged – and bought back hundreds of thousands of existing models from buyers.

In Europe there is still a market for diesel cars, but it’s much smaller today than it was a decade ago. The European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA) reported diesel’s market share 10% in January 2025.

In the UK, things are even more drastic. Figures from the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) put diesel’s market share in 2025 so far at just 5.8% - down 10% on 2024. That’s against the backdrop of much greater uptake of hybrid and electric vehicles – EVs made of 25% of new car sales in February, for example.

Which car companies have stopped making diesel cars?

In 2015 only two manufacturers (Lexus and Smart) didn’t offer diesel models in their ranges.

Fast forward to mid-2024 and the choice of new diesel models for sale has drastically declined. Around half of the mainstream car brands have killed off diesel engines entirely. And the exodus continues in 2025.

Companies that have removed all diesel engines from their lineup include Vauxhall, Toyota, Hyundai, Fiat, Nissan, Dacia, Honda, MINI, Suzuki, MG, Jeep and Volvo.

While some car brands continue to offer diesel models, their choice has greatly reduced. Ford, for example, offered ten diesel models in 2020 and now has just two. Volkswagen offered 17 different diesels in 2020 and now has five, while Renault and Kia offer just one diesel option in their larger cars.

There are a few brands still clinging on to diesel offerings, but these aren’t expected to last beyond the next few years. These include BMW, Mercedes, Audi and Land Rover – the latter still has quite a healthy diesel mix of sales.

However, all of these manufacturers have made long-term commitments to phase out diesel, alongside moving from pure petrol to hybrid and electric models.

Does diesel have a future?

While there’s no doubt that diesel’s popularity has greatly shrunk in the last few years, don’t expect it to go away completely any time soon.

For starters, the Department for Transport reports there were just under 11 million licenced diesel cars on UK roads. That’s not including the millions of diesel vans, lorries and HGVs on the roads each day.

It will take many years for those vehicles to be replaced by hybrid or electric models, bar the government effectively having to remove them from the roads.

In terms of new diesel vehicles, high-mileage drivers will likely continue to choose them where the options remain. And on the commercial vehicle side, while electric vans and lorries are gaining traction, diesel is still the dominant fuel for new vehicles.

But the regulators will force their hand eventually. The mooted petrol and diesel car ban may come in as early as 2030 but could be subject to change, according to today’s Labour government. Meanwhile, all vans will have to be zero emissions by 2035.

But even then, we don’t expect fuel forecourts to suddenly remove the black pump any time soon.

Diesel emissions FAQs

Can I still drive my diesel car after 2030?

Yes, you can still drive your diesel car after 2030. The planned petrol and diesel ban only applies to the sale of new cars – currently there are no plans to remove used diesel cars from the road.

Is it wise to buy a diesel car now?

It depends on your circumstances. Newer, 2015-on diesels are much less polluting and not subject to any Clean Air Zone fines or city bans. However, diesel cars older than that emit high levels of harmful pollutants, and you’ll either pay a charge or be banned entirely from cities across Europe and the UK.

How long will diesel cars be ULEZ compliant?

The Government hasn’t confirmed any plans to upgrade the emissions standards for London’s ULEZ zone. Diesels that meet Euro 6 emissions standards (after 2015) aren’t subject to the charge.